Computers could be like humans in every respect. They could have the intelligence to understand Shakespeare's plays, Napoleon's military strategy, Einstein's theories of relativity. They could have the creativity to paint pictures and compose symphonies, design buildings and invent devices. They could be appreciative of humour and beauty, sensitive to criticism and compassion, motivated by curiosity and ego. And computers could be conscious in the same way as humans. Such computers do not currently exist, but they will.

This book is about humans and computers, creativity, emotions and consciousness. It is about the intriguing possibility that the computers of the future will be as worthy of the epithet 'human' as their human creators.

Buy it from amazon.co.uk

Buy it from amazon.co.uk

Buy it from amazon.ca

Buy it from amazon.ca

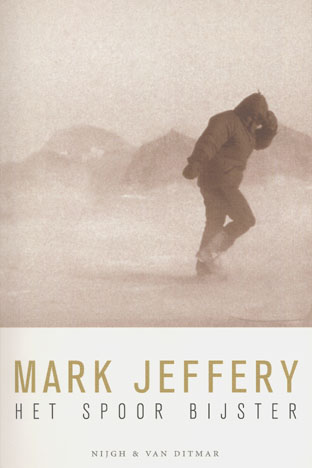

In 1997, Mark Jeffery sets sail for Rothera, a remote Antarctic base, to work as a meteorologist for the British Antarctic Survey. The atmosphere among his colleagues is tense, sometimes even hostile, and the base leadership can be rather authoritarian.

In the ice-cold winter of 1999, Mark Jeffery goes with colleague Lesley Thomson for what should have been a weekend to Lagoon Island, five kilometers from Rothera across Ryder Bay. Soon after their arrival, the sea freezes over, preventing Mark and Lesley's return to Rothera. For three weeks they remain in their hut, cut off from everybody and everything. With the fuel running low and the batteries for radio contact almost spent, the pair begin to suffer hypothermia, frostbite and, through a faulty kerosine stove, carbon monoxide poisoning.

No help comes from Rothera. The longer Mark and Lesley remain on Lagoon Island, the more they fear for their lives, so they decide to walk, against British Antarctic Survey rules, across the sea ice to base. Has the base leadership lost all grip on the reality and become obsessed with the rules and regulations? Or are Mark and Lesley so exhausted and paralysed with fear that they can no longer think straight…

Losing the Plot is currently only available in Dutch

In 1997 vertrekt Mark Jeffery per boot om tweeënhalf jaar op het afgelegen Rothera, de Britse zuidpoolbasis, te werken als meteoroloog voor de British Atlantic Survey (BAS). De sfeer onder de medewerkers laat te wensen over, is soms zelfs vijandig, en de leiding van de basis vertoont nogal autoritaire trekken.

In de ijskoude winter van 1999 gaat Mark Jeffery met collega Lesley Thomson voor wat een weekend had moeten duren naar Lagoon Island, vijf kilometer van Rothera verwijderd en afgescheiden door Ryder Bay. Algauw blijkt dat door het dichtvriezen van de zee Mark en Lesley niet kunnen terugkeren naar Rothera. Drie weken lang bivakeren ze in hun hut - van alles en iedereen afgesneden. De twee hebben nauwelijks nog brandstof, de batterijen voor radiocontact zijn bijna op, ze lijden aan onderkoeling en bevriezing en door een niet goed werkende petroleumkachel lopen ze koolstofmonoxidevergiftiging op.

Hulp vanuit Rothera blijft uit. Langer op Lagoon Island blijven betekent bijna zeker hun dood en daarom besluiten Mark en Lesley, tegen de regels van de BAS in, over het ijs naar het basiskamp te lopen. Heeft de BAS-leiding elke greep op de werkelijkheid verloren en wordt nu krampachtig vastgehouden aan regels en wetten? Of zijn Mark en Lesley zozeer door uitputting en angst verlamd dat ze zelf niet meer kunnen inschatten wat de beste beslissing is...

It's not that everything you've ever thought is wrong.

It's worse than that. Everything you've ever thought

is preventing you from thinking again.

Imagine being imprisoned in a dark cell. You see nothing, hear nothing, feel nothing of the outside world.

Your only contact with the outside is through a prison guard. The trouble is, this guard never tells you straight what he sees in the world. Instead, he interprets what he sees in terms of his own, peculiar ideas about life.

Some things he misses completely: the colour of the autumn leaves, the leap of a cat on to a fence, the furrow of an old woman's brow. Other things he twists subtly to conform to his own ideas: he reports not the words people say, but what he thinks they mean; he describes not the moves people make, but what he imagines are their motives. Sometimes his ideas are so skewed that he tells you the exact opposite of what's real: it may be that outsiders look on you, locked in your cell, with compassion, but your prison guard may insist that they are hostile.

You have no way of telling what's true and what's twisted, because you know nothing of the world other than what the guard tells you.

Here's the bad news. You really are imprisoned in that dark cell. The prison guard is your own mind.

Here's even worse news. The peculiar ideas your mind has about life were formed many years ago, and haven't changed much since. And because you know nothing of the world other than what your mind tells you, and because what your mind tells you is filtered and distorted to conform to those stale, old ideas, they're not likely to change much in future, either. You could be in that prison cell for life.

But here's the good news. Because the prison guard is your own mind, you can tell him to get out of your way, so that you can step out into the world.

You can choose to start seeing again, thinking again, living again, without those stale, old ideas coming between you and reality. You can change your mind.

All you have to do is let go of your fixed ideas.

All you have to do is open your eyes.

Out Of Your Mind is a transitional work in the author's journey from non-fiction to fiction

Mark Jeffery was born in London, England. Since graduating from Corpus Christi College, Oxford University, he has worked as a software developer on a variety of cutting-edge projects, from film editing to photonics simulation. He has travelled the seven continents, including Antarctica, where he spent two years as a meteorologist with the British Antarctic Survey. He now lives in Rossland, BC, Canada.